Patient Case

A 53-year-old male presents to the ICU as a transfer from outside hospital where he presented for low back pain that started after an injury at work. The patient is a mechanic and reports lifting a heavy vehicle door and hearing a pop in conjunction with acute onset pain in the low back which radiated to the RLE. The patient was seen in ED following the injury and underwent CT of the lumbar spine which was unremarkable. He was diagnosed with lumbosacral strain and discharged with pain medications. He re-presented earlier this evening for worsening symptoms and difficulty ambulating due to pain. At the outside facility, the patient was noted to be markedly hyponatremic to 107 and was transferred to our facility for ICU-level care. The patient denies any urinary retention, abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, fevers, chest pain, or syncope. Endorses history of EtOH use– drinks about 1 gallon of ‘gin and tonic’ daily. Denies recreational drug use. No other medical problems. Aside from hyponatremia, the patent’s lab work reveals a WBC of 26.

Overnight, the patient developed coffee-ground emesis and a CT abdomen/pelvis was performed which showed a left psoas abscess and possible osteomyelitis of L4 and L5 vertebrae. MRI the following day demonstrated L4-L5 osteomyelitis discitis with left greater than right psoas/iliac abscesses. S1 paravertebral abscess, posterior epidural abscess at L5-S1, anterior epidural abscesses at T11-L2 and L4-S1.

This patient’s only risk factor for spinal epidural abscess (SEA) was alcohol use disorder. He did not present with fever or focal neurologic deficits. The diagnosis was ultimately made by incidental findings on CT for acute GI bleeding. This patient was an excellent opportunity to review the diagnosis and emergent management of SEA, an uncommon but life- and limb-threatening cause of back pain.

Background

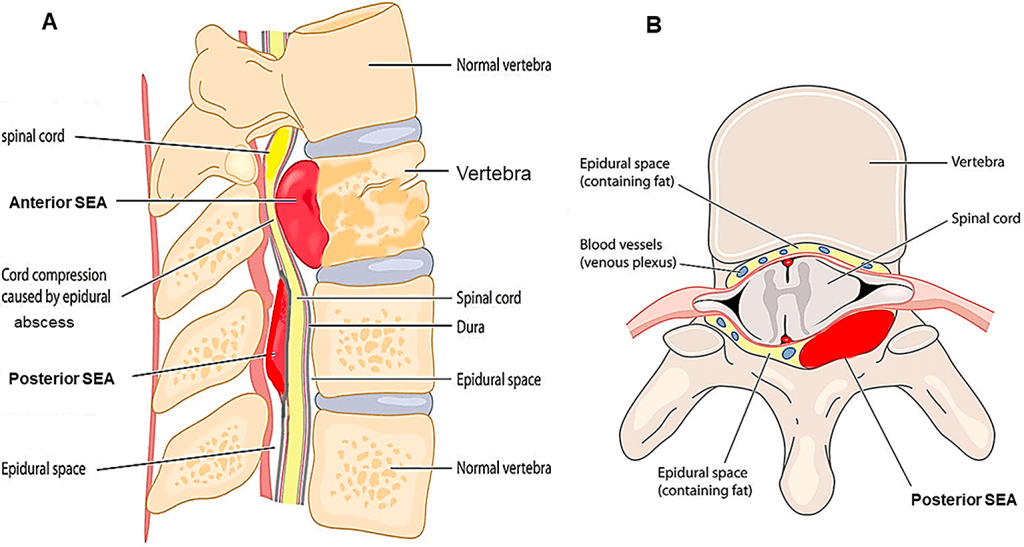

SEA Usually begins as a focal vertebral disc infection which expands and can lead to cord compression (Figure 1). Infection is seeded by hematogenous spread (e.g. bacteremia), iatrogenic inoculation (anesthetic procedures, LP, spinal surgery), or direct extension (e.g. from vertebral osteomyelitis or discitis).

1/3 of patients will have no identifiable source.

Spinal cord damage occurs via compression, thrombosis of nearby veins, arterial blood supply interruption, toxin-mediated damage.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism (63%).

Clinical Presentation

The “classic triad” of fever, back pain, and neurological deficits is only present in about 10% of cases.

Consider SEA in any patient with back pain who is also immunosuppressed, an IV drug user, diabetic, or who has an active infection (UTI, indwelling foley). In our patient’s case, the elevated WBC count and back pain should trigger suspicion.

“Red flag” symptoms are less commonly found on exam. Saddle anesthesia is only seen in about 2% of patients with SEA. Bowel incontinence or reduced rectal tone in just 5-10%. However, the nonspecific findings are much more common—focal tenderness (52-62%) and weakness (29-40%). This serves to remind us that the absence of red-flag symptoms does not exclude critical diagnoses.

Diagnosis

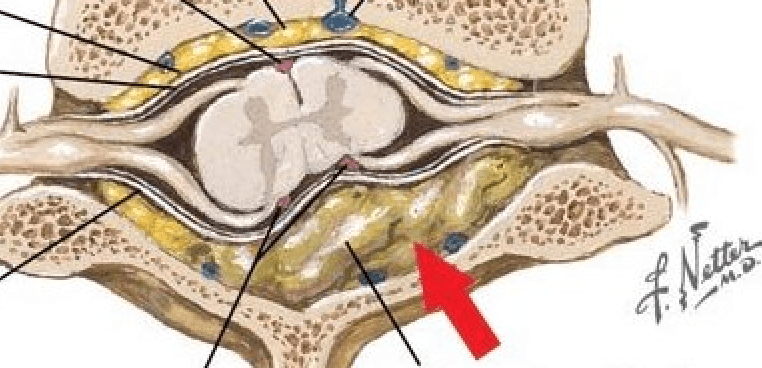

The imaging of choice is MRI with and without contrast (Figure 2). CT myelography is an alternative.

Ideally, image the whole spine. Skip lesions are not uncommon in SEA, and multi-level findings may alter surgical management. Don’t let radiology dissuade you because a total spine MRI is a lengthy procedure. It is indicated and necessary.

Figure 2. MRI of Spinal Epidural Abscess

Management

IV antibiotics are critical and should be given as soon as possible. Vancomycin 30 mg/kg loading dose and Zosyn 4.5g IV initially. Obtain blood cultures, ESR, CRP, CBC, and any other pre-operative labs ASAP. Do not delay antibiotics for cultures of any kind.

Consult neurosurgery or orthopedics (whoever is responsible for spinal interventions at the institution), as any drainable fluid collection or pathology associated with the neurological deficit will likely go to the OR. If you have a patient with a compressive collection, deficits, and no NSGY or quick transfer available, consult IR for possible drain placement as a temporizing measure. Patients with SEA will require ICU admission due to frequent neurologic checks. Don’t forget to bladder scan and place a foley as needed for retention.

Written by: Megan Meade, MD

Reviewed by: Stevley Koshy, MD and Zoran Kvrgic, MD

References:

Myers Bennett. Non-Traumatic Back Disorders. In: Mattu A and Swadron S, ed. CorePendium. Burbank, CA: CorePendium, LLC. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recykAz7FXz1tuD8l/Non-Traumatic-Back-Disorders#h.wak5jz4oldqm. Updated May 5, 2022. Accessed June 15, 2023.

Schubert R, Spinal epidural abscess. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 16 Jun 2023) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-14692.

Sexton, D. J., & Sampson, J. H. (n.d.). Spinal epidural abscess. S. B. Calderwood & J. Mitty (Eds.),. Retrieved June 12, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/spinal-epidural-abscess?search=epidural%20abscess&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~120&usage_type=default&display_rank=1.

Tetsuka S, Suzuki T, Ogawa T, Hashimoto R, Kato H. Spinal Epidural Abscess: A Review Highlighting Early Diagnosis and Management. JMA J. 2020;3(1):29-40.

You must be logged in to post a comment.