Case: 45 y/o healthy male with no significant pmhx who presents to the ER with complaints of RLE pain/swelling over the past 2 days. States he was recently on a road trip to Montana with the family and after returning home, noticed the symptoms. Denies any SOB, chest pain, fevers, chills, dizziness, or changes in vision. States he attempts to work-out regularly and eat healthy. Has never had these symptoms before in the past.

Physician: Patient is well appearing and in no acute distress. VS are hemodynamically stable. Lungs clear to auscultation, cardiac exam benign. When you take a look at his right leg, you notice circumferential swelling and redness from the foot to just below the knee. There is TTP of the calf. Patient has good capillary refill and 2+ pedal pulses b/l.

So just what we all expect, this patient had a duplex venous US performed showing a DVT in the RLE. Given the patient’s recent travel and benign medical history, the DVT was likely provoked in the setting of prolonged inactivity. Patient is otherwise well appearing with no evidence of PE or respiratory distress.

THE QUESTION WE SHOULD ASK NOW: WHAT MAKES A PATIENT A GOOD CANDIDATE FOR OUTPATIENT ANTICOAGULATION IN TREATMENT OF ACUTE DVT?

Let’s start with the basics. What is a VTE: a VTE (venous thromboembolism) is when a thrombus forms in the deep veins commonly in the extremities thus occluding venous return to the heart. Symptoms ensuing include pain swelling, erythema, cramping, soreness, and/or purplish discoloration. The biggest concern for a VTE is embolization to the lungs causing an even more concerning pulmonary embolism which can lead to respiratory distress/failure, right heart strain, cardiovascular collapse, and ultimately, death.

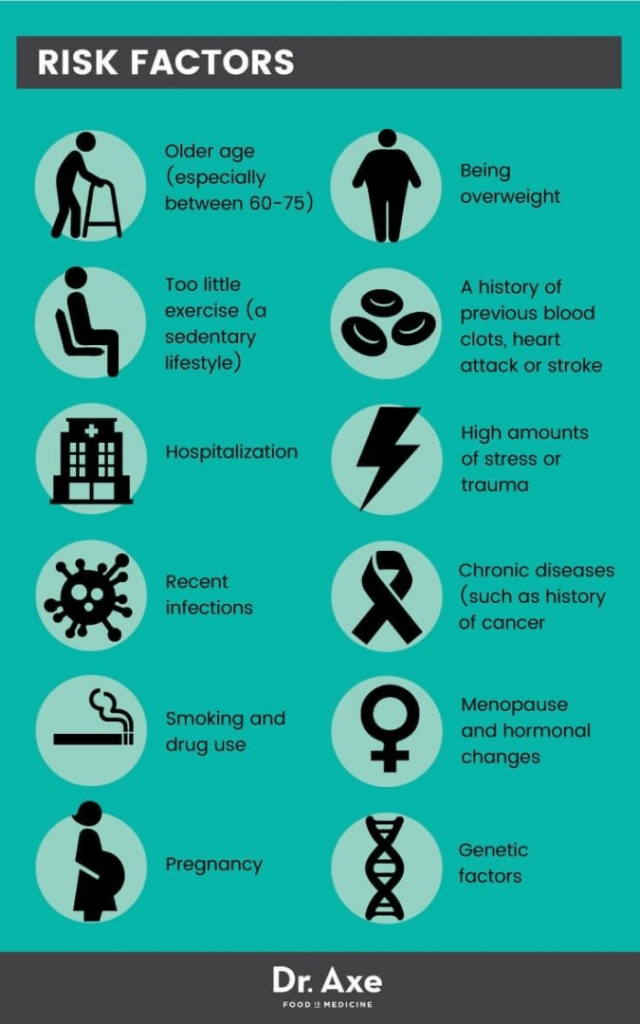

What are a few of the risk factors for determining whether a patient with a DVT is likely to suffer from a recurrent DVT and/or PE?

In addition to the most obvious risk factors, we must also remember comorbidities/circumstances that increased a patient’s risk of VTE including ESRD/dialysis patients, atrial fibrillation, hospitalized or nursing home patients, recent surgeries etc.

How can we risk stratify acute VTE (DVT) patients (LOW vs HIGH risk)? Relatively no good scoring systems are exist at this time. A few others that have been created are for use in specific populations not applicable to newly diagnosed VTE (DVT) in the ER but can be used as generalized references.

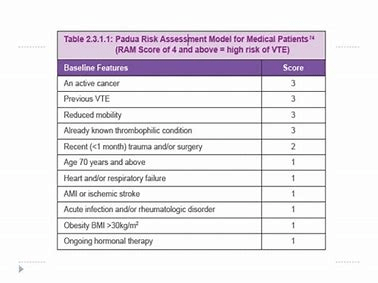

Padua Prediction Score for Risk of VTE – This scoring system was created to determine the need for prophylactic anti-coagulation for hospitalized patients. Poor applicability to the use of a/c for outpatient treatment for known VTE.

DASH Prediction Score for Recurrent VTE – Developed for use in patients previously diagnosed with VTE who have completed a 3-6 month course of anticoagulation, DASH Scores ≤1 are associated with 3.1% annual recurrence, which may be low enough to consider discontinuing anticoagulation. Conversely, patients with DASH Scores ≥2 are at high risk for recurrent VTE and may require long-term anticoagulation.

Hestia Criteria for Outpatient Pulmonary Embolism Treatment – Only applicable to patients with acute PE.

In 2018, the American College of Emergency Physicians published a clinical policy discussing the recommendations to support the appropriate management of patients in the ER with acute VTE. [1] The critical question asked was “In adult patients diagnosed with acute lower extremity DVT who are discharged from the ED, is treatment with a NOAC safe and effective compared with treatment with LMWH and VKA?”

Both Level B and C (see below**) recommendations suggest that in selected patients with acute DVT, a NOAC may be used as a safe and effective alternative treatment to LMWH/VKA.[1] Within the selected 259 articles identified as part of creating this clinical policy, one study published specifically addressed the safety and efficacy outcomes of patients with acute VTE discharged directly from the ER on a NOAC.[2] In the study, 271 patients were identified with acute VTE, 39% considered low risk and discharged on PO rivaroxaban. Low-risk patients were based on a modified version of the Hestia Criteria as discussed previously. 51% represented new acute DVT diagnoses and 27% new PE diagnoses. No patient discharged on oral rivaroxaban had recurrent VTE or a clinically relevant bleeding event while receiving therapy (95% CI 0% to 3.4%). [2]

**Level B recommendations. Recommendations for patient care that may identify a particular strategy or range of strategies that reflect moderate clinical certainty (eg, based on evidence from 1 or more Class of Evidence II studies or strong consensus of Class of Evidence III studies).el C recommendations. Recommendations for patient care that are based on evidence from Class of Evidence III studies or, in the absence of any adequate published literature, based on expert consensus. In instances where consensus recommendations are made, “consensus” is placed in parentheses at the end of the recommendation. The recommendations and evidence synthesis were then reviewed and revised by the Clinical Policies Committee, which was informed by additional evidence or context gained from reviewers

What are the implications of these policies and outpatient treatment regimen for patients with newly diagnosed VTE?

- Reduced inpatient treatment-related complications (eg, hospital-acquired infections)

- Reduced cost compared with inpatient care or medication monitoring of VKAs

- Reduced hospital inpatient crowding

- Reduced time associated with treatment follow-up

- Better use of health care resources

- Improved patient satisfaction because of more efficient patient care and the ability to be treated at home

- Improved safety profile of NOACs with reduced major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding compared with standard therapy [1]

How can you incorporate this into your clinical practice now?

There are many resources available to use as clinical guidelines in addition to your own clinical gestalt when determining if a patient with acute VTE (DVT) is a candidate for outpatient anticoagulation. Important external factors to consider as well include:

- Patient’s understanding of strict treatment adherence

- Patient’s social support

- Close PCP follow-up

- Patient is at low risk for falls and is counseled on fall precautions

Medicine has changed drastically in the past few years. We are seeing sicker patients with lower health literacy. Hospitals are overrun and understaffed. Our goal as physicians is to always provide the highest quality treatment to our patients. But what changes can we implement that continue to provide high-quality treatment to our patients, improve patient satisfaction, and lower admission rates/unnecessary hospital costs?

Next time you diagnose a patient with acute VTE (DVT), consider if the patient is a good candidate for outpatient anticoagulation.

THE END

Written by: Alexandra Sheriff, MD

Reviewed by: Stevley Koshy, MD

Works Cited

- Wolf et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Suspected Acute Venous Thromboembolic Disease. Annals of Emerg Med. 2018. Vol 1 (5): 59-109.

- Beam DM, Kahler ZP, Kline JA. Immediate discharge and home treatment with rivaroxaban of low-risk venous thromboembolism diagnosed in two US emergency departments: a one-year preplanned analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015; 22:789-795.

You must be logged in to post a comment.