CASE

A 34 year old female, presents to the emergency department with complaints of right shin pain and swelling. Symptoms started 3 weeks ago, persisted, and have not improved. The patient denies preceding trauma. A review of symptoms is otherwise unremarkable. X-ray to evaluate for fractures and ultrasound of lower extremities to evaluate for Deep Vein Thrombosis were both unremarkable. The patient was also treated for cellulitis with appropriate oral antibiotics and time course, without relief. The patient has a history of hypothyroidism and polycystic ovarian syndrome but is otherwise healthy.

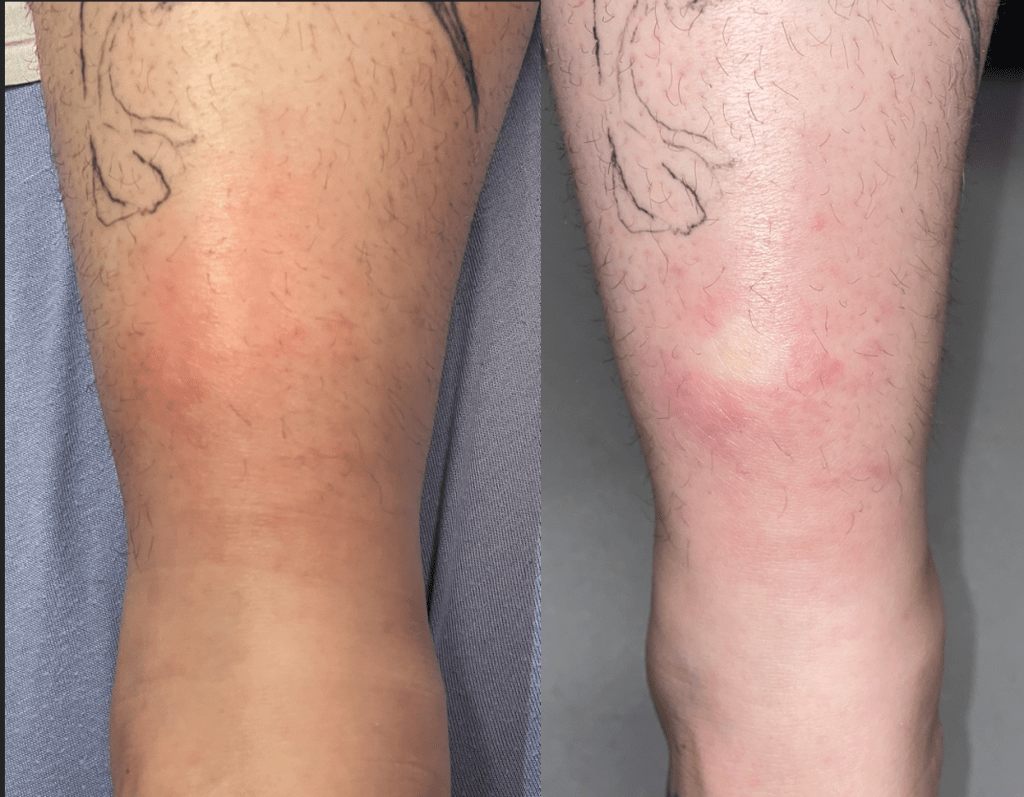

A physical exam reveals a 4cm, lesion on the right lower anterior shin. The lesion is erythematous, raised, and tender (Figure 1). Lesion is non pruritic and is blanching. (Figure 2). No other lesions are present in either lower extremity.

Given that symptoms have not improved with Tylenol and Ibuprofen therapy, the patient was given a prescription of Percocet 5mg tablets for breakthrough pain and advised to follow up with a primary care physician for a referral to a dermatologist and further evaluation of Erythema Nodosum associated conditions.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Erythema Nodosum (EN) presents most commonly in women in 20 to 40s. Women are 3-6 times more likely to be affected than men.

SYMPTOMS

Nodules are tender, ill-defined, nonulcerated, immobile, slightly raised, typically 2-5cm in diameter, can coalesce, and are located on bilateral shins. Nodules can be preceded by nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, fever, malaise, arthralgias, and upper respiratory infection symptoms.

PATHOLOGY

EN is mostly composed of panniculitis, an infection of subcutaneous adipose tissue. It is believed to be a delayed type of hypersensitivity reaction. Pathogenesis is not fully understood and there are multiple complex mechanisms involved, including TNF alpha production, granuloma formation, immune complex deposition, and reactive oxygen species formation.

ETIOLOGY

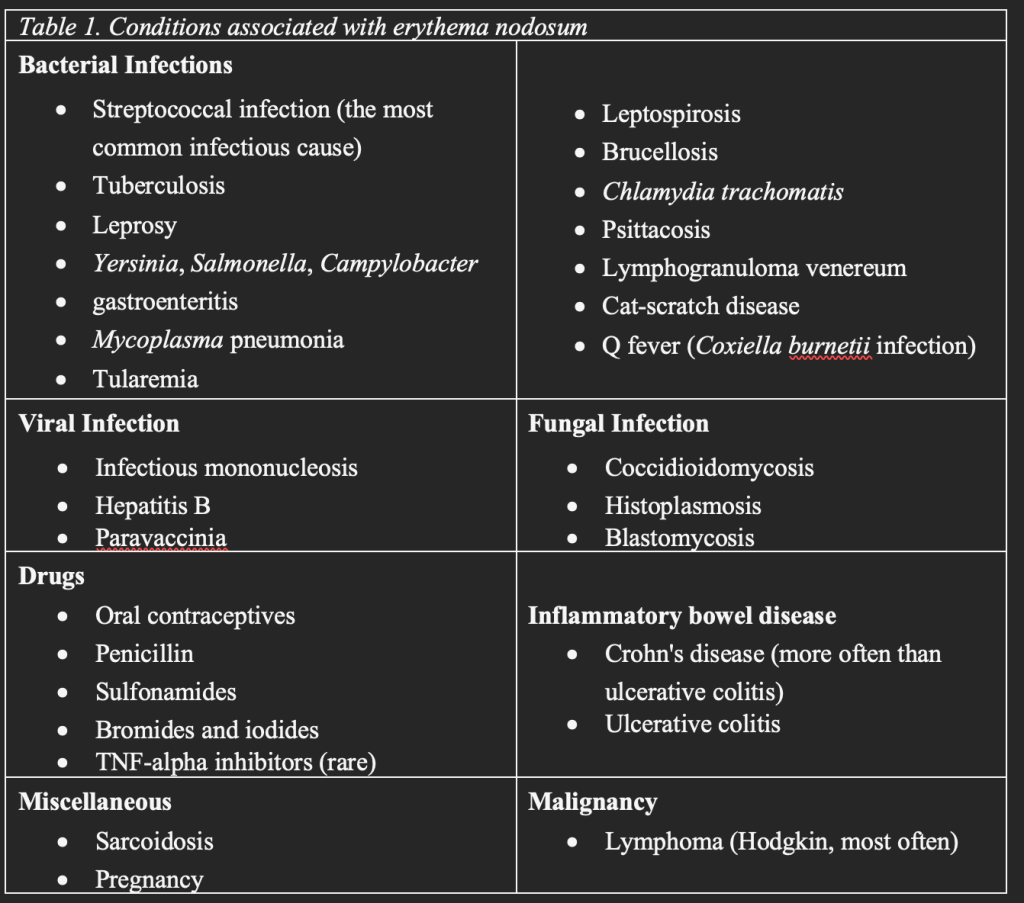

There are numerous underlying conditions that are associated with erythema nodosum (Table 1), notably sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and most commonly streptococcal infection.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is clinical, based on history and physical examination. Skin biopsy can assist in confirming the diagnosis, especially in atypical presentation. Laboratory testing is largely nonspecific and not often utilized in the emergency department (ED). However, patients should be further evaluated for underlying medical conditions (Table 1) and in the majority of cases, it is appropriate to conduct in the outpatient setting. Differential diagnoses include nodular vasculitis, subcutaneous bacterial or fungal infections, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, malignancy, and pancreatic panniculitis.

TREATMENTS

Most nodules self-resolve spontaneously within 8 weeks of presentations. Some nodules will leave behind bruising, known as Erythema Contusiformis, and this hyperpigmentation may take months to resolve. There are no randomized trials for interventions against EN. Treatment is mainly supportive care which can include:

- General measures: leg elevation, rest, compression.

- Treatment of associated conditions.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: First-line therapy. evidence for NSAID use mainly stems from small case series and reports. No one NSAID is preferred over the other. Their use should be cautioned if patients with inflammatory bowel disease, as they may exacerbate this condition.

- Potassium Iodide (KI): KI has been shown to rapidly improve symptoms of EN and completely resolve within a few days. Evidence for KI comes from small uncontrolled studies. KI is dosed at 300mg TID. If symptoms do not improve within 2-3 weeks, treatment may be discontinued. If symptoms improve progressively, the patient may continue treatment until full resolution. KI use should be cautioned in patients with known pulmonary tuberculosis or those taking KI supplements.

- Glucocorticoid therapy: A 7-day course of oral Prednisone 20mg daily can be tried to treat EN, but an optimal regimen has not been established. This therapy can be helpful if the patient also has underlying IBD.

- Corticosteroid injections: A single dose of triamcinolone acetonide may be injected in the center of the nodule with a response seen within 1 week. Concentration of 10-20mg/ml is used. Potential adverse effects of atrophy and hypopigmentation of the skin should be weighed against the benefits of therapy.

- Other therapies that have shown some efficacy but would be less likely utilized in ED: Dapsone, Colchicine, Hydroxychloroquine, and TNF inhibitors.

DISPOSITION

- Treatment is based on clinical judgment.

- Follow up with primary care doctor for evaluation of underlying associated conditions.

- Follow up with Dermatologist.

DISCUSSION

Our patient largely had a classic presentation of Erythema Nodosum given the symptoms as well as the age and sex of the patient. However, there were atypical features such as unilateral involvement, only one nodule present, as well as refractoriness of NSAID treatment. During the visit, there were no identifiable risk factors, and the patient was not taking any Oral Contraceptives at that time, which has been associated with EN. Ultimately, the patient was appropriately referred for outpatient evaluation of underlying conditions.

Interestingly, the patient was evaluated for DVTs and fractures, and was also treated for cellulitis. It is unclear whether these measures were appropriate at that time, given that they were performed in an outpatient setting, prior to presentation to ED. There was no preceding trauma to suspect a fracture. Also, there were no identifiable major risk factors for DVT in this patient, which typically presents more with posterior calf swelling and tenderness. Cellulitis on the other hand is also an erythematous, tender, and poorly demarcated skin lesion. In conclusion, we acknowledge the challenges of diagnosis EN, which is largely a clinical diagnosis, and that providers can reasonably choose to exclude other conditions such as fracture, DVT, and cellulitis given they are more common and easily evaluated for.

Lastly, in the ED our patient did not receive any additional treatment listed for erythema nodosum. It would have been reasonable to pursue other treatment measures since NSAID therapy did not provide relief, and patient’s quality of life was being adversely affected by the condition. The reason for hesitancy to prescribe additional treatment is unclear. We can presume that some providers are not as comfortable treating this condition because it is not very common and additional therapy is not often prescribed. A well known and generally safe therapies such as glucocorticoids and potassium iodide would have been a rational option. However, this condition is self-limited, so focusing on pain control with NSAIDs and Percocet was a practical approach.

TAKEAWAYS

- Treatment of the underlying conditions is the most important part of management.

- NSAIDs are the first line of therapy.

- Prednisone daily can be used if the infection has been excluded.

Written by: Zoran Kvrgic, MD

Reviewed by: Stevley Koshy, MD

REFERENCES:

- Hanauer SB. How do I treat erythema nodosum, aphthous ulcerations, and pyoderma gangrenosum? Inflamm Bowel Dis 1998; 4:70; discussion 73.

- Schulz EJ, Whiting DA. Treatment of erythema nodosum and nodular vasculitis with potassium iodide. Br J Dermatol 1976; 94:75.

- Potassium iodide and streptomycin for tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 1949; 240:664.

- Sterling JB, Heymann WR. Potassium iodide in dermatology: a 19th century drug for the 21st century-uses, pharmacology, adverse effects, and contraindications. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 43:691.

- Winter HS. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, and aphthous ulcerations. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1998; 4:71.

- Tremaine WJ. Treatment of erythema nodosum, aphthous stomatitis, and pyoderma gangrenosum in patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1998; 4:68.

- Bondi EE, Margolis DJ, Lazarus GS. Panniculitis. In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 5th ed, Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al (Eds), McGraw-Hill, New York 1999. p.1284.

- White WL, Hitchcock MG. Diagnosis: erythema nodosum or not? Semin Cutan Med Surg 1999; 18:47.

- Cox NH, Jorizzo JL, Bourke JF, Savage CO. Vasculitis, neutrophilic dermatoses and related disorders. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology, 8th ed, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C (Eds), Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken 2010. Vol 3, p.50.1.

- Patterson JW. Panniculitis. In: Dermatology, 3rd ed, Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV (Eds), Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia 2012. p.1641.

- Kunz M, Beutel S, Bröcker E. Leucocyte activation in erythema nodosum. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999; 24:396.

- Tintinalli, Judith. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine. 8th ed., McGraw Hill, 2016.