Case

A mid 60s female patient was brought into the emergency department via ambulance after a motor vehicle accident that occurred 20 minutes prior in which she was the restrained driver. She has known past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity. The accident occurred on a residential street where the patient reportedly was driving erratically at less than 20 mph and side-swiped several vehicles before coming to a complete stop on the curb. Per EMS, she was able to self-extricate from the vehicle but had a very unsteady gait and reported significant dizziness. On interview the patient states that she was driving home from getting lunch and had a rapid onset of dizziness and nausea that immediately preceded the accident. She describes the dizziness as “the whole world started spinning around” her. The patient denies ever having these symptoms in the past.

Background

Dizziness is one of the common chief complaints that emergency medicine physicians evaluate on shift. The etiology of the dizziness can range from benign to life-threatening and it is our role to figure out which it is in a timely manner. More benign causes of dizziness include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), which is a peripheral cause. More life-threatening and potentially permanently disabling is the posterior cerebrovascular accident (CVA), which is a central cause.

In the United States, about 795,000 people annually have a stroke or CVA, about 185,000 are in people who have never had a CVA in the past. 87% are ischemic, and 20% of all ischemic events involve the posterior circulation of the brain.

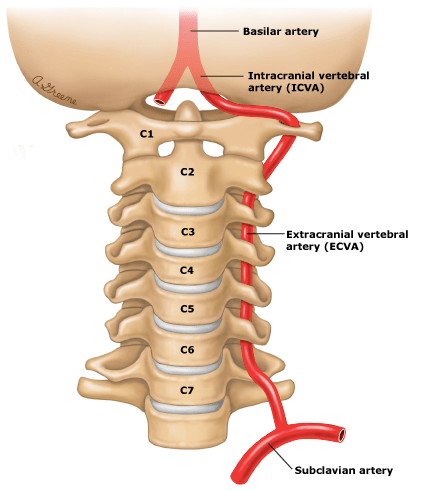

Posterior CVAs can occur due to stenosis or occlusion of the innominate and subclavian arteries in the chest, the vertebral arteries in the neck, and posterior cerebral, basilar or their smaller branch arteries in the cranium. Given that the ischemic Posterior CVA can be treated with thrombolytic therapies such as alteplase and tenecteplase if the patient meets criteria, the emergency physician needs to quickly assess if the patient’s dizziness is from a central or peripheral cause. One of the most useful and often confounding tools in our armament for the evaluation of the acutely dizzy patient with nystagmus is the HINTS exam.

Take the HINTS

The head impulse-nystagmus-test of skew (HINTS) exam is a 3 component exam whose findings when combined together have demonstrated 100% sensitivity and 96% specificity in diagnosing posterior CVA. The HINTS exam has also demonstrated to be more sensitive than MRI in the first 24 hours. The confounding components of the HINTS exam include on whom to perform the exam, how to properly perform it, and how to correctly interpret the results.

The HINTS exam must be performed only on a patient who has nystagmus and is currently symptomatic with vertigo/dizziness, nausea or vomiting, or unsteady gait.

Head Impulse

While the Head Impulse (HI) test is the first part of the HINTS mnemonic, it is best performed last in the exam because symptomatic patients often have worsening of nausea symptoms with the rapid head movement required for this component of the exam. The patient is asked to start with their head turned horizontally about 10 degrees away from center and focus on the distant target or object. Next, the examiner rapidly turns the head horizontally 15 degrees in the opposite direction. In an abnormal HI test, when the patient’s head is turned it is unable to keep focus on the fixed target, instead, the eyes undergo a “corrective saccade”, meaning that the eye’s focus is taken off the target and then they slowly beat back to again focus on the distant target. In a normal HI test, the patient’s head is quickly turned and the eyes are able to keep focus on the distant target without moving. The confounding nature of interpreting this component of the HINTS exam is that a normal HI test is indicative of a central cause for the patient’s symptoms such as posterior CVA. An abnormal HI test is more indicative of a peripheral cause such as vestibular neuritis.

Nystagmus

In the evaluation of central v. peripheral causes for a patient’s nystagmus and symptoms of dizziness, the emergency physician needs to determine if the nystagmus is unidirectional or bidirectional. First, we need to see to which side is the nystagmus beating. After the direction is determined the patient should look in the direction of the beating nystagmus. In rightward beating nystagmus, the patient should look laterally to the right, and vice-versa. In peripheral causes of nystagmus, when the patient looks toward the side of beating, the nystagmus should become more pronounced. Additionally, when the patient looks to the side opposite the beating, the nystagmus should lessen or resolve altogether, this is a unidirectional nystagmus. In central causes of nystagmus, the nystagmus will become more pronounced when the patient looks in the direction of the beating, and when the patient looks in the opposite direction, the nystagmus will change direction as well. In central causes, a rightward beating nystagmus will become more pronounced when looking toward the right, and will change direction to a leftward beating nystagmus when looking to the left. This is bidirectional or direction-changing nystagmus.

Test of Skew

Assessing for skew deviation is likely the easiest component of the HINTS exam. In a test of skew, the examiner covers one of the patient’s eyes then quickly uncovers it while covering the other eye. A positive test of skew is seen when uncovering the eye and it is vertically misaligned from the center before quickly returning to center. A negative test of skew is seen when uncovering the eye and the eye is aligned in the center. A positive test is associated with central causes such as posterior CVA.

Any 1 central finding when performing the HINTS exam raises the likelihood that symptoms are due to a posterior CVA, and further testing or treatment is indicated. MRI with diffusion weighted imaging remains the gold standard imaging modality in diagnosing an ischemic stroke. However, in the first 24 hours of symptoms, the HINTS exam is more sensitive at diagnosing posterior compared with MRIs given the possibility of false negatives on imaging in the initial time frame. Like with anterior circulation acute ischemic CVAs, patients with posterior CVAs who present within the treatment window should be assessed to determine if thrombolytic therapy is indicated. When thoroughly understood and applied, the HINTS exam may just be one of the most useful tools in the emergency physician’s toolkit in assessing the acutely dizzy and vertiginous patient especially when the patient’s balance hangs in the balance.

Back to the Case

The patient appears disoriented and keeps her eyes closed during the physical exam because she claims the light and movement make her want to vomit. On ocular exam there appears to be a fast horizontal nystagmus that beats to the left when the patient looks left and to the right when the patient looks right. When the examiner cover the patients right and left eyes they notice no abnormalities in terms of vertical alignment. When the examiner tells the patient to focus on the clock directly just to the left of her and attempts to turn the head the patient’s eyes remain fixed on the clock, they subsequently vomit. Given the presence of 2 central findings on the HINTS exam, the patient is diagnosed with posterior CVA, and because she has presented to the ED within 1 hour of symptom onset, she is a candidate for thrombolytic therapy. The patient is administered tenecteplase per protocol and subsequently admitted to the ICU for further monitoring.

Written by: Harshal Lal, DO

Peer Reviewed and Edited by: Stevely Koshy, DO

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying Cause of Death, 1999–2018. CDC WONDER Online Database. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Accessed March 30, 2022

Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009;40:3504–3510