Introduction:

As medicine is ever changing, new diseases and symptomatology are being classified differently according to the etiology, presentation, clinical findings, and treatments of subsets of disease pathology. There have been various names throughout the continued advancement of medicine for acute pulmonary edema, but there have also been various clinical findings and differences in treatments as well. Now considered the most modern and accurate description is sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema which is one of these newer entities that varies slightly to many other types of pulmonary edema and has gone by many other names such as flash pulmonary edema, hypertensive acute heart failure, and now SCAPE. Depending on the journals or literature you are reviewing, these names are all identifying the same disease pathology, with slight variations.

Defining SCAPE:

Sudden onset pulmonary edema in the setting of hypertension most often meeting criteria for hypertensive emergency, which is defined as severe hypertension with end organ damage, the end organ being “damaged” in this case is the finding of acute pulmonary edema. Generally, these patients have little to no peripheral edema as they have preserved right ventricle ejection fraction. This is opposite to your classic heart failure patients that generally present with jugular venous distension (JVD), pulmonary edema, and peripheral edema in the setting of previous congestive heart failure (CHF) diagnosed. The other difference is the onset of symptoms as SCAPE is rapid and usually less than 12 hours, whereas a CHF exacerbation or fluid overload accumulates over many days to weeks.

Risk Factors and Associations:

- Elderly > 65 YO

- Pre-existing heart failure

- Previous episodes of SCAPE

- Renal artery stenosis

Pathophysiology:

The general underlying feature that occurs is increased sympathetic response or sympathetic overload which causes excessive increase in afterload with vasoconstriction, and thereby increasing the work of the heart and raising blood pressure to dangerous levels. This is a dangerous cycle as the sympathetic tone is increased, the systemic vasculature constricts causing a rise in blood pressure and increased work on the heart. Secondary to the increased work on the heart there is an even further rise in sympathetic tone in both inotropic and chronotropic effects, and further repeating this loop.

Clinical Presentation:

- Rapid onset severe dyspnea

- Hypoxia/Hypoxemia

- Tachypnea and Tachycardia

- Hypertension often exceeding 160/120 and occasionally > 180/120 (HTN emergency with findings of end-organ damage)

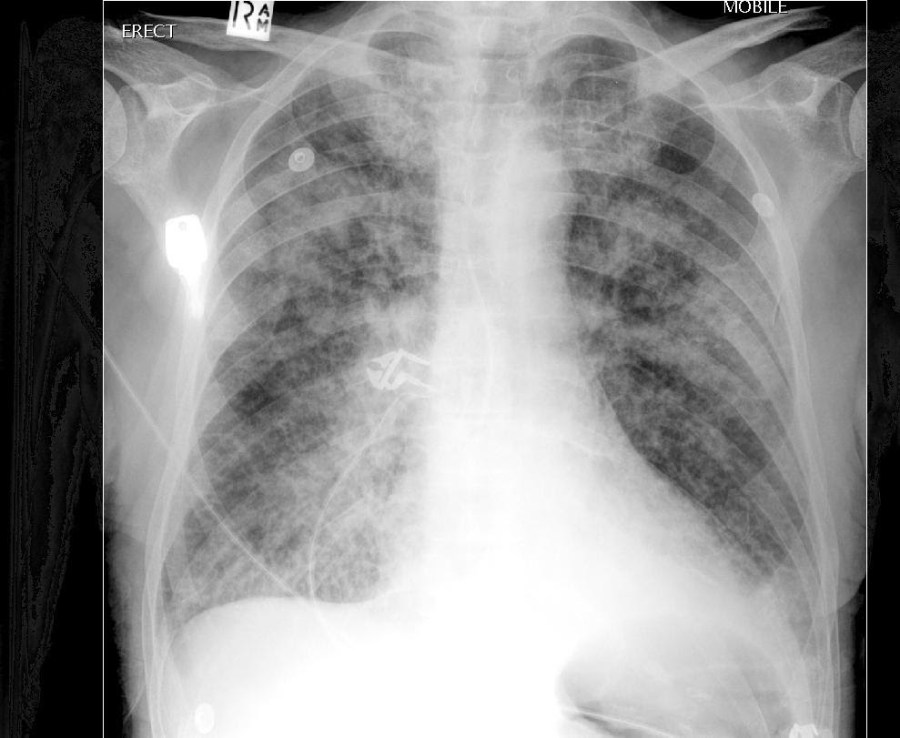

- Diffuse pulmonary edema on CXR with diffuse rales on physical examination

- Occasionally “pink frothy sputum”

- Little to no peripheral edema and no JVD

Lab Workup:

Often irrelevant in managing the acute illness as this patient is on the verge of cardiovascular collapse secondary to high sympathetic activation. Often these patients look extremely ill and end up in the ICU/step-down level of care. However, some suggested workup for these patients is like a normal cardiac workup:

- CBC, CMP, Troponin, COVID swab

- EKG: often showing sinus tachycardia without other findings

- Bedside ECHO with pulmonary window: decreased EF, patchy pulmonary B-lines (unlike the diffuse B-lines of CHF exacerbations), and inferior vena cava (IVC) may not be dilated and often has respiratory variation:

- Contrast this with usual CHF exacerbations and fluid overload where there is usually marked IVC dilation and little to no respiratory variation

- Chest X-ray: diffuse pulmonary edema

Treatment:

- Aggressive administration of CPAP/BiPAP with high expiratory pressures (some critical care experts state that either type is appropriate or can benefit the patient with little differences in this pathology):

- CPAP: 15-18 cm

- BiPAP: 18/8 cm

- Aggressive administration of Nitroglycerin in high doses:

- Remember that this pathology has happened acutely and is not chronic and therefore your guidelines of 25% MAP reduction in Hypertensive Emergency does not apply here

- Any form of nitro whether paste or subglingual, however the key is to convert as rapidly as you can to a nitroglycerin drip

- Some experts starting nitroglycerin drip around 100-300 mcg/min (if you remember the calculation of 3 Nitro tabs SL 0.4 mg over 15 minutes, it comes out to 80 mcg/min, so don’t be afraid to start high)

- Some consider 75% absorption in the equation and adjust this starting dose of the Nitro drip to 60 mcg/min

- Recommended titration is to maintain a SBP < 140 mmHg

- Often after reaching this goal, you can just as aggressively wean off nitroglycerin drip

- Other medications that can be considered if the above is not effective are:

- Afterload reduction with IV Calcium Channel Blockers such as nicardipine or IV ACE-inhibitors such as enalaprilat, however availability of these medications is not widespread

- Consider pain medications for “air hunger” when titrating CPAP/BiPAP as often these patients are agitated or altered

- A hallmark of SCAPE is that there is rapid improvement with the appropriate treatments. If not improving rapidly, consider alternate etiologies.

Take Home Points:

- Rapid onset (< 12 hours) and not the typical findings of CHF on examination and studies

- Often no JVD, peripheral edema, or IVC dilation on POCUS

- No need to adhere to HTN emergency protocols of MAP reduction of 25% as this is such an acute event and goal SBP < 140 mmHg

- Rapid and aggressive administration of CPAP/BiPAP and Nitroglycerin

- Rapid improvement with appropriate treatments

Written By: William Hall IV, MD

Peer Reviewed and Edited By: Rossi Brown, DO

References:

- Sympathetic Crashing Acute Pulmonary Edema. Agrawal N, Kumar A, Aggarwal P, Jamshed N. Sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2016;20(12):719-723. doi:10.4103/0972-5229.195710. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5225773/

- Collins SP, Levy PD, Martindale JL, Dunlap ME, Storrow AB, Pang PS, Albert NM, Felker GM, Fermann GJ, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollander JE, Lanfear DJ, Lenihan DJ, Lindenfeld JM, Peacock WF, Sawyer DB, Teerlink JR, Butler J. Clinical and Research Considerations for Patients With Hypertensive Acute Heart Failure: A Consensus Statement from the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine and the Heart Failure Society of America Acute Heart Failure Working Group. J Card Fail. 2016 Aug;22(8):618-27. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.04.015. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27262665/

- Collins S, Martindale J. Optimizing Hypertensive Acute Heart Failure Management with Afterload Reduction. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018 Feb 24;20(1):9. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0809-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29478124/

- Stemple K, DeWitt KM, Porter BA, Sheeser M, Blohm E, Bisanzo M. High-dose nitroglycerin infusion for the management of sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema (SCAPE): A case series. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Jun;44:262-266. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.03.062. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32278569/

- Sympathetic Crashing Acute Pulmonary Edema. Farkas J, Weingart S. https://emcrit.org/ibcc/scape/