26 year old male of filipino descent presents with diffuse motor weakness that was present upon waking this morning at 0400. Patient reports he was of normal health and asymptomatic last night and in the preceding days. Patient denied recent infectious symptoms such as diarrhea, cough, congestion, fevers, chills, urinary changes, rashes or insect bites. Patient reported he ate a large burrito for dinner last night.

Primary assessment patients airway was patent, breathing spontaneously, with intact distal pulses.

Vital signs on arrival were BP 131/96. HR 67. RR 18. 99% on RA. 37C. Patient was calm and in no acute distress, breathing spontaneously. Neurologic exam revealed Cranial nerves II to IX intact. There was flaccid paralysis of all extremities which involved the proximal and distal muscles, greater in lower extremities than upper. Sensation was intact throughout all dermatomes. Deep tendon reflexes were diminished to 1 out of 4 patellar, 2 out of 4 supinator and triceps.

Initial labs venous blood glass with critical care panel was obtained showed pH 7.36, pCO2 43, PO2 49, HCO3 24.3, sodium 139, potassium 1.2, glucose 109, ionized calcium 4.3. Complete metabolic panel showed Sodium 140, potassium 1.6, chloride 106, carbon dioxide 22, glucose 113, urea 13, creatinine 0.8, magnesium 2.2, phophorus 2.2, calcium 8.7, albumin 4.7, anion gap 12, liver enzymes and complete blood count were within normal limits.

Differential diagnosis includes several causes of acute motor weakness including neurological causes such as cerebrovascular accident, seizure, myasthenia gravis, cataplexy. There inflammatory causes, or metabolic myopathies, such as poly- and dermatomyositis. In a first attack of quadriparesis, other diagnoses such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, acute myelopathy (eg, transverse myelitis), myasthenic crisis, tick paralysis, and botulism should be considered.

Luckily, this patient was medically inclined therefore he was calm at presentation and already had an understanding of his condition noting he had one prior similar episode and a few other minor episodes. He new that his attack was precipitated by a large carbohydrate laden burrito the night before for dinner.

In a case like this the finding of hypokalemia generally alerts the clinician to the diagnosis of hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Additionally, in an attack of hypokalemic periodic paralysis bulbar and extraocular muscles are rarely ever affect compared to other causes of acute quadraparesis. In an acute attack, the diagnosis of familial hypokalemic periodic paralysis is supported by hypokalemia and excluding thyrotoxicosis and secondary causes of hypokalemia.

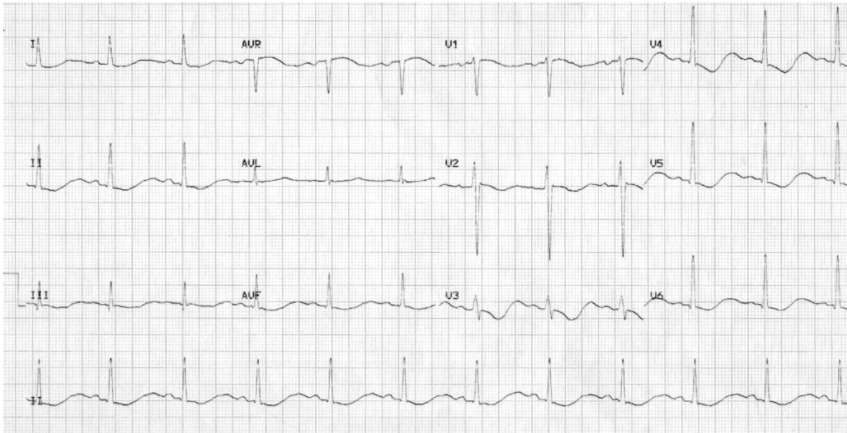

To review, an electrocardiogram may show increased P wave amplitude, prolongation of PR interval, widespread ST depression and T wave flattening/inversion, prominent U waves (best seen in the precordial leads V2-V3, and a “apparent” long QT interval due to fusion of T and U waves (= long QU interval).

The treatment of acute attack hypokalemic PP begins with oral administration of 60 to 120 mEq of potassium chloride, given incrementally, which usually aborts the attack. Recovery can be seen minutes, but can take a few hours. Treatment should be administered incrementally, to reduce risk of posttreatment hyperkalemia, and levels should be monitored for 24 hours. A suggested protocol is potassium chloride 30 mEq orally every 30 minutes until serum potassium normalizes. However, some recommend slower rates of administration (10 mEq per hour), to minimize rebound hyperkalemia.

Interestingly, mild attacks can be aborted by low-level exercise.

Written by: Taylor Brittan, MD

Peer reviewed by: Hakkam Zaghmout, MD

- Fontaine B. Periodic paralysis. Adv Genet 2008; 63:3.

- Venance SL, Cannon SC, Fialho D, et al. The primary periodic paralyses: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Brain 2006; 129:8.

- Lin SH, Lin YF, Chen DT, et al. Laboratory tests to determine the cause of hypokalemia and paralysis. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164:1561.

You must be logged in to post a comment.