A 64 y.o patient with a history of ALS presents to the ED with shortness of breath. On exam, he is alert but appears to be taking shallow respirations. He has a history of chronic diaphragmatic weakness secondary to his ALS and is on NIPPV at night. His saturation is 94% on room air. You place him on oxygen to see if it will help his respiratory effort. Are there any bedside tests that can be performed to predict his need for further respiratory support?

Respiratory Muscle Weakness

Neurological disorders such as Guillain-Barré, myasthenia gravis, and ALS can cause both acute and chronic respiratory muscle weakness. Especially in Guillain-Barré, rapid respiratory muscle weakness can develop and if not caught in time can lead to ventilatory failure and death. A normal saturation on the pulse ox does not predict the need for further respiratory support. If a provider waits until there is respiratory distress or desaturation, it may be too late.

Respiratory Parameters

Several respiratory parameters can be checked by a respiratory therapist at the bedside:

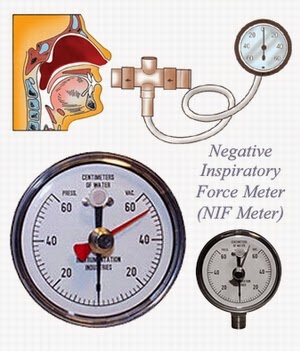

- MIP (NIF) – maximal inspiratory pressure. The amount of force the patient can generate while breathing in is measured. This mainly measures diaphragmatic strength.

- MEP – maximal expiratory pressure. The opposite of MIP, this is the pressure the patient can generate while exhaling. This is used to assess the ability of the patient to cough and clear secretions.

- FVC – forced vital capacity. This is the total amount of volume the patient can exhale after taking maximal inhalation. This measures inspiratory strength, expiratory strength, and lung compliance.

Test Interpretation

The 20 – 30 – 40 rule is used to remember the values to beware of for respiratory parameter monitoring and when the patient falls below these values, it may be an indication for more aggressive intervention.

- FVC should be > 20ml/kg

- MIP should be > 30 cmH20

- MEP should be > 40 cmH20

Putting it all Together

When you have a patient at risk for respiratory muscle weakness, you need to be aggressive to avoid rapid respiratory failure. A respiratory therapist can perform these tests at the bedside with readily available equipment. Previously MIP (NIF) and MEP were used, but they are more patient effort dependent and less reproducible than FVC. FVC is the best test for ventilatory capability given that it integrates diaphragmatic strength, respiratory muscle strength, and lung compliance. If you are going to get one test, get the FVC.

Remember that a normal pulse ox does not necessarily exclude the patient from having impending respiratory failure. Ventilatory failure will happen first. We need to be able to predict which patients require ICU level airway monitoring so that they do not decompensate on the floor.

Patients whose respiratory parameters fall near or below these cutoffs should be monitored in an ICU and considered for elective intubation. These values however do not mandate intubation. With the advances in NIPPV and HHFNC, patients should be started on these first (NIPPV preferred). They help with respiratory effort and can prevent further respiratory muscle fatigue. In order for these to work effectively however, they need to be initiated before the patient is in extremis which is why it is important to obtain respiratory parameters and predict which patients are at increased risk for respiratory decompensation.

Take home:

- Be aggressive with patients at risk for respiratory muscle weakness (ALS, GBS, MG)

- Ask respiratory therapy to obtain bedside respiratory parameters

- Initiate NIPPV early

- Consider ICU monitoring for patients with abnormal parameters

Author:

Timothy Beau Stokes, MD

You must be logged in to post a comment.