A 38 year old female with no PMH presents from home by EMS with AMS. The patient’s last known normal was 4 hours PTA. EMS reports that family says she was initially screaming out in pain and screaming “help me” for about 30 minutes before EMS was called. Family did report mild headache for the 3 days prior to this event. When EMS arrived at the home the patient was unresponsive, but did withdraw to pain. Upon arrival to the emergency department she had worsened and had a GCS of 3.

Initial VS in the ED were: BP 226/133, pulse 52, resp 10, O2 sat 100%. BVM in process.

Given the GCS of 3, she was intubated with etomidate and rocuronium without complication. Initial vent settings were TV 450, RR 18 (goal to initially mildly hyperventilate), FiO2 40%. Pt started on propofol.

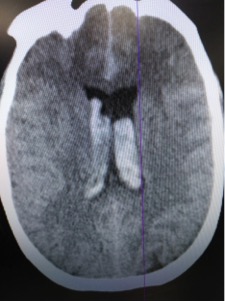

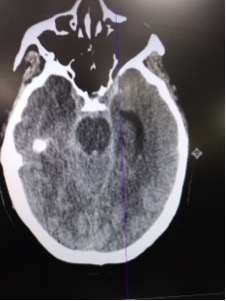

Patient was rushed to CT given clinical hx and presentation.

CT read as large amount of subarachnoid hemorrhage, suspicious for ruptured aneurysm.

Neurosurgery was emergently consulted and recommended transfer to tertiary center for further care. Keppra for seizure prophylaxis was given. BP spontaneously reduced to 117 systolic. Transport was arranged.

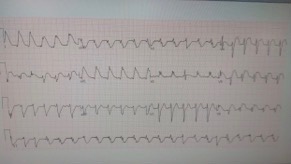

While waiting for transport the patient experienced a marked change in her cardiac monitor. EKG was obtained:

The EKG showed diffuse ST elevation, markedly changed from prior. These changes were determined to be related to SAH rather than an acute STEMI. The EKG returned to normal about 20 minutes later.

While awaiting transport, she also started to have changes in her neuro exam. Her pupils changed from 5mm and reactive bilaterally to L 7mm and R 9mm and nonreactive. It was assumed this was from impending herniation and neurosurgery was consulted again. It was recommended to start mannitol however the patient was unable to tolerate this as she became rapidly hypotensive and required norepinephrine vasopressor support.

The patient survived transport but unfortunately expired within 24 hours of arrival to receiving facility.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Twenty percent of strokes are hemorrhagic, with subarachnoid hemorrhage and intracerebral hemorrhage making up to 10 percent each. Most SAHs are caused by ruptured saccular aneurysms, which have mortality rates near 50 percent as well as significant neurologic morbidity in survivors. Approximately 10 percent of patients with aneurysmal SAH die prior to reaching the hospital, 25 percent die within 24 hours, and about 45 percent die within 30 days.

Classic clinical presentation

- Sudden, severe headache – “Worst headache of my life“

- Altered level of consciousness

- Collapse or vomiting at onset

- Meningismus

- Preretinal subhyaloid hemorrhages

- Mild lateralizing neurologic signs

- Sudden and severe headache that precedes current event by 6 to 20 days.

- Most frequent ECG abnormalities are ST segment depression, QT interval prolongation, deep symmetric T wave inversions, and prominent U waves.

Diagnosis

- Noncontrast head computed tomography (CT) – most sensitive in the first 6 to 12 hours after SAH

- Lumbar puncture – is mandatory if there is a strong suspicion of SAH despite a normal head CT

- SAH is eliminated if both are performed within 48 hours and negative

Interpreting LP

- Classic findings of SAH are an elevated opening pressure and an elevated red blood cell count

- The lack of significant decline in RBC between tubes one and four, and immediate centrifugation of the CSF can help differentiate bleeding due to SAH vs that due to a traumatic spinal tap.

- Clearing of Blood → likely traumatic tap

- Xanthochromia → likely SAH

Misdiagnosis occurs when there is:

- Failure to appreciate the spectrum of clinical presentation associated with SAH

- Failure to obtain a head CT scan or to understand its limitations in diagnosing SAH

- Failure to perform a lumbar puncture and correctly interpret the results

Things that lead to these errors include – small SAH volume, normal mental status at presentation, and right-sided aneurysm location.

Treatment

- Early consult to neurosurgery

- Stop and reverse anticoagulation if necessary – vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, or unactivated prothrombin complex concentrate

- Labetalol, nicardipine, or enalapril to lower blood pressure to <140 mm Hg (or as recommended by neurosurgery)

- Avoid nitroprusside or nitroglycerin due to tendency to increase cerebral blood volume and therefore intracranial pressure

- Osmotic therapy and diuresis if elevated ICP is evident

- Hypertonic saline or Mannitol. Studies have shown that hypertonic saline boluses are more effective at lowering ICP, however long term outcomes are not clear.

- Furosemide can be given with mannitol to increase effect, however this may worsen dehydration and hypokalemia.

- Maintain Euvolemia to prevent refractive ischemia

- Intubation if necessary – GCS ≤8, elevated ICP, poor oxygenation or hypoventilation, hemodynamic instability and requirement for heavy sedation or paralysis.

- Hyperventilation with mechanical ventilation to lower PaCO2 to 26 to 30 mmHg can rapidly reduce ICP through vasoconstriction and a decrease in the volume of intracranial blood. With this, post injury acidosis may also be buffered due to the respiratory alkalosis.

- Prophylactic antiepileptic drug therapy is not required in all patients, but may be considered in some with unsecured aneurysms and large concentrations of blood at the cortex.

- Avoid phenytoin due to association with worse neurologic and cognitive outcome after SAH

Complications

- Rebleeding

- Vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia

- Hydrocephalus

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Seizures

- Hypothalamic dysfunction – will likely cause hyponatremia

- Cardiac abnormalities

- EKG abnormalities, LV dysfunction, elevated troponins and BNP

Attending Discussion:

There are a lot of moving parts to this unfortunate case. The patient essentially presented with acute worsening of her headache after having several days of mild headache that rapidly progressed to altered mental status and coma. The initial vital signs are concerning for developing increased ICP with hypertension and bradycardia. Based on the initial GCS of 3 and concern for acute intracranial hemorrhage and impending herniation, rapid intubation, CT imaging, hyperventilation, and mannitol all make sense. The EKG findings in this case are very interesting and have been known to be associated with intracranial bleeding. ST elevation, deep precordial t wave inversions, and arrythmias can all be present in the setting of intracranial hemorrhage. This case had two ongoing critical pathologies – SAH which required managemetn as well as increased ICP.

Managing SAH:

- SAH is one of the intracranial bleeds that does benefit from BP reduction. The typical goal BP is 140 systolic. The classic agent used in the ED is nicardipine and because tight control is needed, consider an arterial line for these patients.

- The dreaded complication from aneursymal SAH is delayed vascospasm that will result in a stroke. Nimodipine should be given to prevent this (but does not necessarily need to be given in the ED).

- Reverse anticoagulation if appropriate

- Do NOT give platelets to reverse antiplatelet agents. This actually will INCREASE mortality.

- Antiepileptic agents are controversial and should be discussed with your consultant.

- Literature supports non contrasted CT to rule out SAH if obtained within 6 hours of headache onset. The caveat to this is that it needs to be the most current generation CT and it needs to be read by a fellowship trained neuroradiologist.

- CTA does not rule out SAH

- LP interpretation can be difficult. Xanthocromia is concerning but lack of xanthrocromia does not necessarily mean traumatic tap. Reduction in RBCs from tube 1 to 4 does not necessarily mean no SAH. Unfortuantely there is no well validated criteria for LP interprtation to definitively differentiate between traumatic tap and SAH. We have to use our best judgement based on what we see and the clinical scenario.

Managing increased ICP:

- Osmotic diuresis with mannitol or hypertonic saline should be performed early.

- A brief trial of hyperventilation can be performed as a last resort, however beware that prolonged hyperventilation will actually cause rebound/paradoxical increased ICP and worsen outcomes.

- Elevate the head of the bed as much as possible.

- If there is a cervical collar, take it off if you can.

- If intubated, the patient needs to be completely sedated. If necessary, paralyze the patient.

- Pre-treatment with lidocaine during intubation is controversial.

A brief note on TBI/cerebral edema/intracranial hemorrhage in general:

To appropriately treat the above pathologies, we really need to understand cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). CPP is the differece between the MAP and the ICP and is essentially a measurement of the perfusion the brain is currently getting. Our goal is to keep this >60 (if the patient has an ICP monitor this can accurately be measured but otherwise we are just keeping the concepts/theories in mind). If ICP rises, we risk reducing the CPP. If MAP falls, we risk reducing the CPP. There are times in the ICU where patients actually require vasopressors even without hypotension to maintain CPP depending on the ICP.

The reason all this is important is because as discussed above, we need to do everything we can to lower ICP to maintain CPP. This includes avoiding hypercarbia and hypoxia which will greatly increase ICP. We also need to maintain MAP and avoid hypotension at all costs. Depending on the pathology and hemodynamics of the patient, all of these factors can be complex and difficult to manage at once. Reach out to your neurointensivist early for help.

Authors:

Krista Maier, DO

Peer reviewed and edited by:

Timothy Beau Stokes, MD