Dyspnea and syncope are common complaints seen in the ED. Most of us would not hesitate to add acute coronary syndrome or pulmonary embolism to the differential, but pulmonary hypertension with right heart failure is a differential frequently left off of that list. Although not as common as some of the other causes of dyspnea, missing this in the differential can have detrimental effects on the patient.

The discussion below will be split into two sections – one containing the must know information for managing a RHF patient in the ED, and another for those interested in getting a little nerdier and diving deeper into pulmonary HTN.

What kind of symptoms will these patients present with?

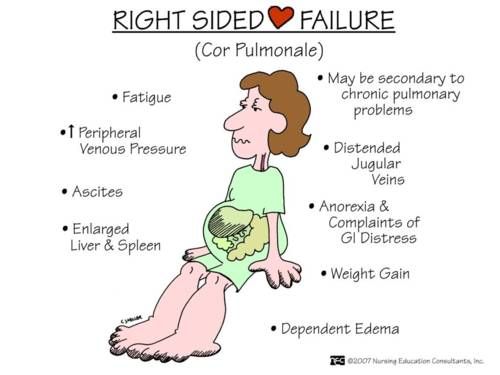

The obvious answer is dyspnea, but especially exertional dyspnea. This is the most common symptom attributable to pulmonary HTN. Patients may also report chest pain from demand ischemia due to impaired coronary perfusion to the right ventricle. As right ventricular failure worsens, patients will present with exertional syncope or pre-syncope secondary to decreasing cardiac output. Classic signs of right ventricular failure such as JVD, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, weight gain, ascites, and edema are seen later in disease progression.

Keep this in the differential of your critically ill patients. Much of our population has CODP and as it worsens our patients can present with cor pulmonale. Treating a shocky COPD patient with cor pulmonale like a normal COPD exacerbation or like a left heart failure patient can lead to disastrous results.

ED evaluation of RV failure

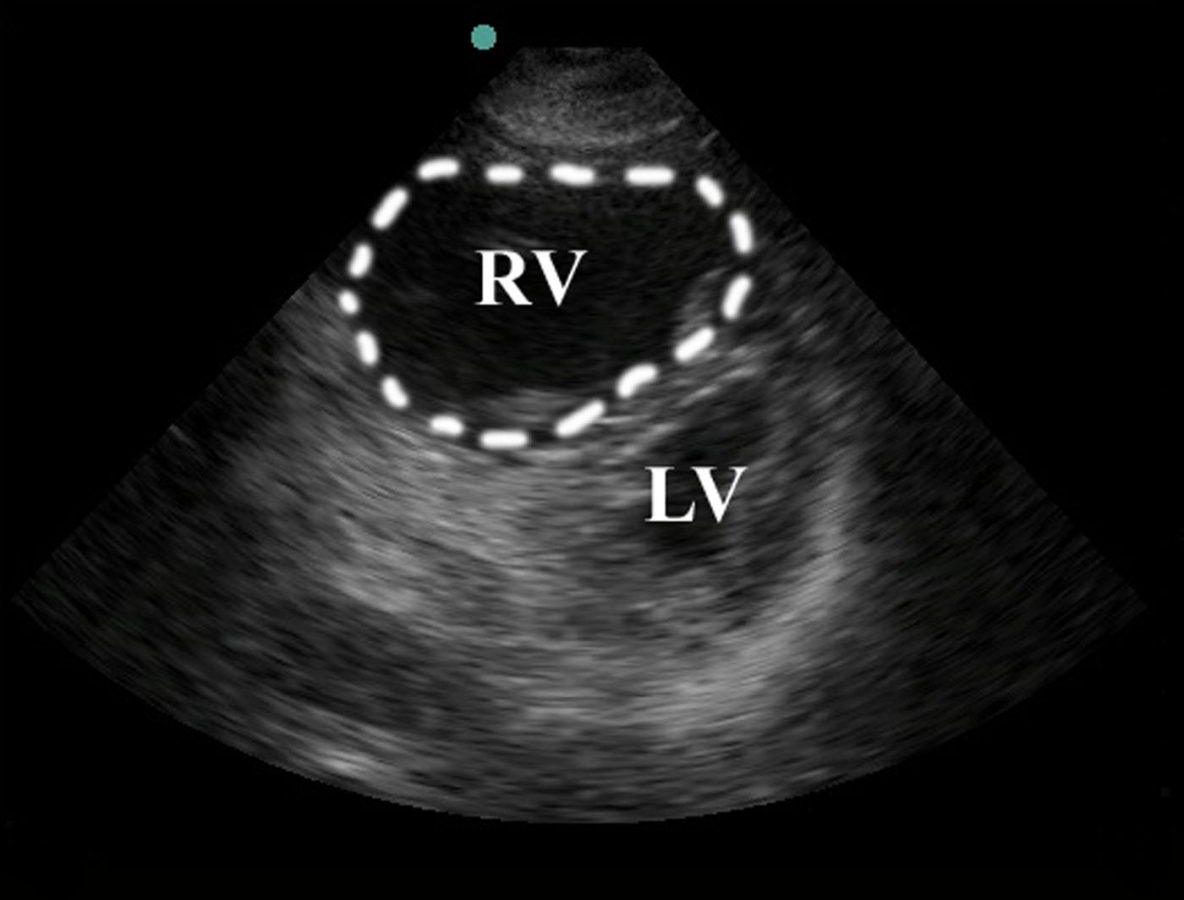

The test of choice for ED evaluation is bedside echo. Although the definitive test for diagnosis of pulmonary HTN with resultant right heart failure is a right heart catheterization, this is unrealistic in the ER setting. On a bedside transthoracic echo, there are certain findings that point the differential towards right heart failure. The first is right ventricular enlargement. Right ventricular enlargement is defined as the right ventricle being greater than two-thirds the size of the LV. Basically if the RV looks the same size or greater than the LV, worry about some sort of RV overload. Another important finding is flattening of the interventricular septum, which is identified by a D-shaped LV when using the parasternal short axis view. The IVC should also be assessed and as a plethoric IVC without variation can point towards increased RV pressure or possibly failure. Other signs of RV failure include tricuspid regurgitation as well as decreased RV contractility.

Treatment

#1: Volume status

This is one of the most important factors in determining treatment pathway i.e. Lasix vs. fluid. It is often one of the most difficult to assess. The goal is to optimize preload very carefully while making sure not to overload. The majority of cases of right ventricle failure are associated with excessive preload and it is wise to err on the side of volume constriction vs. volume expansion. Again, patients are most often overloaded unless there is an obvious source or reason for volume loss. In the case where there is an obvious source of volume depletion, only bolus small volumes such as 250ml should be used as these patients can quickly become overloaded and their hemodynamics are tenuous. This should be done with repeat reassessments for effects on BP, urine output, etc.

# 2; Maintain perfusion to RV and improve inotropy

The common pathway leading to acute RV failure from multiple causes is RV ischemia. Hypotension needs to be avoided as well as arrhythmias, since patients with RHF cannot tolerate either. Norepinephrine and vasopressin are the pressers of choice to maintain these patients’ MAPs. Norepinephrine not only maintains coronary perfusion pressure but also augments inotropy. Vasopressin has the benefit of decreasing pulmonary vascular resistance when used. Phenylephrine should be avoided as increasing SVR in isolation can lead to hemodynamic collapse. Dobutamine can be considered but should be used in conjunction with norepinephrine to prevent hypotension. Beta blockers and calcium channel blockers should be avoided in the treatment of RHF patients.

#3 Reducing RV afterload

To reduce RV afterload, perform interventions that will lower pulmonary artery pressure. NO is an inhaled pulmonary vasodilator that can decrease pulmonary vascular resistance with minimal effects on SVR. If the patient is already on a systemic pulmonary vasodilator such as prostacyclin (Veletri/Esoprostenol) it is critical that this is continued/not interrupted. However if a patient is not already on one of these medications, they should be avoided/not initiated in critically ill patients.

# 4: Maintain oxygenation and ventilation

Hypoxia should be avoided as this causes pulmonary vasoconstriction and therefore increased pulmonary vascular resistance. Ensure you optimize V/Q mismatch by giving albuterol/ipratropium if indicated. Hypercapnea also causes increased pulmonary vascular resistance and should be aggressively treated.

# 5: Beware of positive pressure

NIPPV and intubation is a double-edged sword. It can have benefit by reducing hypoxia and hypercarbia, but it increases RV afterload and decreases preload, which may worsen RV failure. Intubation is extremely risky in RHF due to the possibility of hemodynamic collapse peri intubation. Intubation with typical RSI results in loss of catecholamines and causes vasodilation, decreased preload, and worsening RV output. Strongly consider awake intubation to avoid peri intubation complications. Minimize PEEP/EPAP. Consider heated high flow nasal cannula if appropriate to minimize the increase in intrathoracic pressure.

The Nerdy Side of Right Heart Failure:

Physiology of Right heart failure:

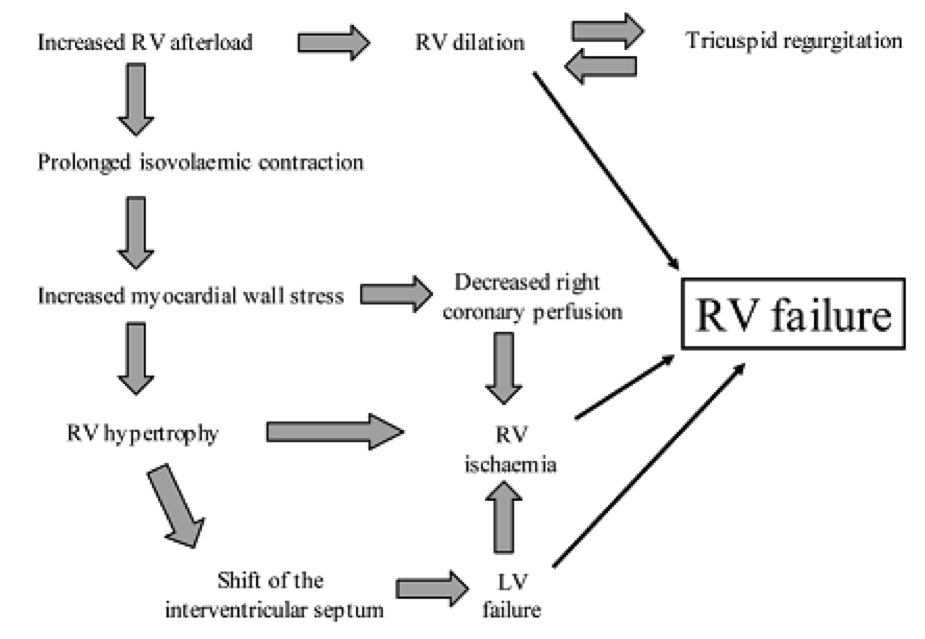

It is important to understand the key differences between the right and left ventricle and how this plays a role in the development of right hear failure. First, the right ventricle (RV) is much less muscular than the left ventricle (LV) and much more compliant then the LV. This is in part due to the fact that the pulmonary vascular resistance (RV afterload) is much less then systemic vascular resistance (LV afterload). Secondly, the RV is very dependent on volume loading. LV contractility is more of a wringing motion versus the RV, which has longitudinal motion using pressure against the septum to aide in contraction. This results in what is called ventricular interdependence. When the LV contracts, motion of the septum aides 20 to 40 percent of the work of contraction of RV. If the RV is failing, it becomes dilated, pushing the septum in the LV, impairing filling.

Right heart failure can be further classified based on physiology

- Increased RV afterload:

- Examples of this etiology include pulmonary arterial HTN, left heart failure causing pulmonary venous HTN, PE, hypoxia (causes pulmonary vasoconstriction), pulmonary stenosis, or being placed on mechanical ventilation

- Impaired RV contractility

- Examples are RV MI, cardiomyopathy, sepsis

- Increased RV preload

- Examples include tricuspid or pulmonary regurgitation, post removal of LVAD, ASD/VSD

- Decreased RV preload

- Examples are SVC syndrome, tricuspid stenosis, tamponade, states of hypovolemia

*An important note is that the common final pathway that results in progressive worsening of RV failure for any of these causes is RV ischemia. Also the most common cause of RHF is LHF, followed by hypoxic lung diseases including COPD, OSA, ect.

Pulmonary Hypertension and how it is classified.

The WHO classifies pulmonary HTN into 5 groups as follows:

Group 1 – pulmonary arterial HTN. This group is familial, idiopathic, formerly known as “primary pulmonary hypertension” or associated with other disease states, including connective tissue diseases, drug or toxin exposures, HIV, or congenital heart disease.

Group 2 – pulmonary hypertension caused by left-sided heart disease. Examples are chronic LV failure, severe mitral valve disease, or severe aortic valve disease.

Group 3 – pulmonary hypertension caused by lung disease or hypoxemia. Examples include COPD, OSA, and obesity hypoventilation syndrome.

Group 4 – pulmonary hypertension from chronic thromboembolic or embolic disease. Examples include history of previous PE, especially recurrent PEs, large PEs, extremes of age, or PH at diagnosis of PE.

Group 5 – miscellaneous. This group is pulmonary hypertension with unclear multifactorial mechanisms and includes patients with mediastinal tumors or adenopathy, sarcoidosis, hemodialysis, thyroid disorders, and vasculitis.

Take Home Points:

- In critically ill patients, keep right heart failure in your differential as its management is different and these patients are tenuous.

- These patients can have hemodynamic collapse from both the addition of fluids or diuresis. Tread carefully.

- Avoid hypotension

- Avoid hypoxia

- Avoid hypercarbia

- Beware of NIPPV and intubation

Attending Commentary – Beau Knows:

Right heart failure is a disease we don’t see all the time, but one we must recognize. We also must have at least a basic understanding about right heart physiology and why the management of this disease is so difficult and why these patients can be so tenuous.

Imagine the heart as two chambers with the lungs acting like a tube of toothpaste:

Now imagine various pathologies as squeezing that tube of toothpaste, making it difficult for things to flow through, and sometimes even causing things to flow backwards:

This is what happens in right heart failure secondary to pulmonary hypertension. However we can exacerbate this squeezing effect iatrogenically and cause hemodynamic collapse if not careful. Things such as placing the patient on Bipap or intubating the patient can cause that toothpaste tube to squeeze because of the increased intrathoracic pressure.

Our interventions should be aimed at “unsqueezing” the toothpaste tube. If the patient had COPD or ILD, we should be using aggressive respiratory therapy with bronchodilators. We should be avoiding hypoxia and hypercarbia at all costs, because these cause pulmonary vascular constriction and will increase the squeeze on the tube. We can also try fancy things such as inhaled NO to decrease the pulmonary vascular resistance.

If airway management is needed, consider trialing heated high flow nasal cannula as the theoretical PEEP is minimum and will squeeze the tube less. If Bipap or intubation are pursued, consider lowering the PEEP if possible to below 5 for the same reason.

Finally, be very careful with volume status in these patients. They are very preload dependent but they also get LV impairment with hypervolemia. This is where bedside echo can greatly assist your management. With a failing RV, we need to be careful with all types of volume interventions and perform smaller than normal interventions at a time with frequent reassessment.

Authors:

Kara Finegan, DO

Peer reviewed and edited by: Timothy Beau Stokes, MD